Folders |

Backstage With Untold Cross Country History: 50 Years Since Richard Kimball's World Junior Gold (Part 1)Published by

California Teen Raced to BreakthroughsThat Paced a Golden AgeBy Marc BloomPart One of Two

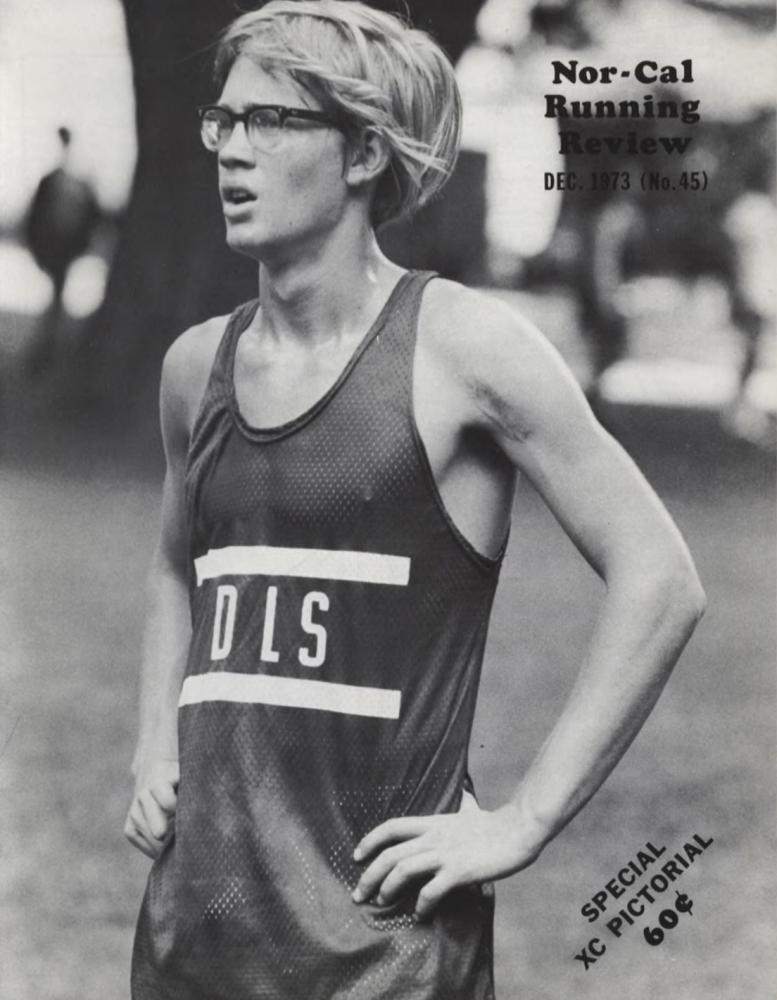

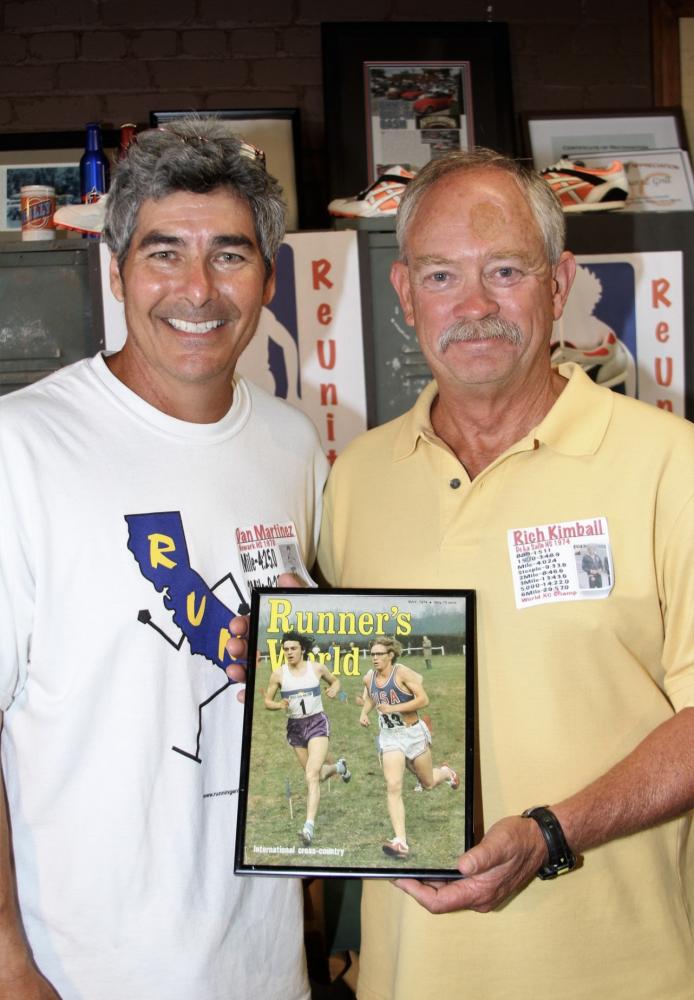

The year was 1974. Running was a big deal in the United States. Marathons were taking off, high school boys were breaking nine minutes for two miles left and right, girls and women could finally compete officially with the passage of Title IX, and it was not unusual to find a “track star” heralded on the cover of Sports Illustrated, then the ultimate imprimatur of athletic success. Steve Prefontaine himself had appeared on the cover of S.I. in 1970. A freshman at the University of Oregon, Pre was hailed with the tag line, “America’s Distance Prodigy.” The previous year, at Marshfield High in Coos Bay, Ore., he’d set a high school outdoor two-mile record of 8:41.5. In 1973, Craig Virgin, from Illinois, went even faster: 8:40.9. That same season of ’73, an emerging talent from northern California, Richard Kimball, made promise out of despair. It was Kimball’s junior year. With the state meet coming up, he chipped a bone in his foot playing pick-up basketball, causing a missed opportunity. The blow shook Kimball, urging him to make a vow as firm as any delivered from a preacher’s pulpit. With that commitment, an extraordinary career took off, ultimately resulting in the cover photo above — to me, more appealing and runner-worthy than any track shot Sports Illustrated ever produced. If there’s one photo that can be said to represent running’s essence — its primitive glory, controlled energy and rhythmic beauty all at once — it’s this memorable May, 1974 cover of Runner’s World, from the 1974 World Cross Country Championships in Monza, Italy. This week, March 16, marks the 50th anniversary of the event, which carries with it much history, embossed in the figure of Kimball, age 17, on the right. It marked the first time a U.S. junior-age cross country team competed abroad, and Kimball made the most of it. How cool does this young man look! Kimball’s Italian rival to his left, Venanzio Ortiz, was also dressed to the nines — reflecting the Italians’ sense of style and, after all, they were running at home (notice Ortiz’ race number: 1). And if I’m playing art director, I can’t help but feel that the patriotic red-white-and-blue of Kimball and showroom blue-white-and-purple of Ortiz, together with the luscious green turf of the Hippodrome course, present a timeless setting stirring the senses rather like the gardens of Monet. I’m a saver, but until I reached out recently to speak with Kimball, and dove into my own files, I’d forgotten this memento, worthy not only of a track fan’s collection but an exhibit signaling a new age of excellence, sustained to this day. This era found fertile ground most particularly in southern California, where at the about same time in the first half of the 1970s, the likes of Ralph Serna, Eric Hulst, Curtis Beck, Terry Williams, Mark Schilling, Jim Schankel, Thom Hunt, and so many others, raced one another and set new levels of achievement, offering, in effect, a challenge to the state’s young men a few hundred miles north via Route 101, to create a history of their own. Richard Kimball took them up on it. “Rich set a standard for us,” said Serna, the nation’s No. 1 miler of 1975, at 4:07.0, and No. 2 at two miles, in 8:46.0 (behind Hulst, 8:45.0). “When I saw that cover, I said I want to run that race next year.” (He did.) “Rich in full stride, with that USA top. Everyone took that to school and showed it around. All the runners found it inspirational. Rich launched a new era.” Perhaps a certain fate blessed the moment. The Monza photographer with the keen eye was a young Mark Shearman of Great Britain, who would become one of the leaders in his field. Shearman was — and is — an artist with a flair for composition, a colleague of mine in the track world who I once linked up with in a summer 10k in Oslo prior to the Bislett Games. But that’s another story. Trivia question: Name the American men who won individual world cross country championships four years in a row, from 1974 through 1977, while leading the U.S. each year to the team gold — a feat equaled only by the Kenyans and Ethiopians in their recent years of domination. Hold that thought. Kimball was something of a paradox. As the oldest of four boys growing up in Rancho Cordova, outside Sacramento, Kimball had a rebellious streak — not the kind that would find him getting into trouble but the opposite: cutting the straight-and-narrow, a fierce adherent to old school goal setting, with an undeterred focus, parochial mass taste be damned. Kimball was his own man.

That, and a race, any race, from a dual meet to the world meet. “Put me on the track,” said Rich, reflecting back. “Shoot the gun, and I’m off. No worries.” Check out Kimball’s muscular physique in the photo. I asked him about weight training. None, he said. “That came from hill running.” And those glasses; they’re almost the first thing you notice. They’re in every vintage photo. “My parents didn’t give me contacts,” he said. The muscles, the glasses, the bulky, nerdy look, the firm, confident stride, the wavy blond locks — Rich Kimball at 17 was sort of matinee idol meets Silicon Valley boy genius. If Kimball had his own genius, it was probably his high threshold for pain. Injuries didn’t stop him; nothing did. Once he ran a two-man, 24-hour relay and, when his partner gave up, Kimball took his partner’s turns as well, amassing a total of 69 miles (most under 5:00) in one day. As a senior, Kimball ran 52 races — dual meets, invitationals; 880, mile, two-mile and mile relay — in three months, commenting now, “It never crossed my mind that I was running too much.” Consider the pivotal basketball injury in the spring of ’73. When the state qualifying meet arrived, Kimball lost his patience, ripped the cast off his foot and ran the mile and two-mile, hoping to make the state finals; lacking training, and still in pain, he just missed the top three to move on. Furious with his bout of bad luck, Kimball vowed to come back as a senior and win both state titles, even though the two events were held close together on the same day. For the next 12 months, Kimball was possessed by that promise. “I was so tired of Southern California winning everything,” he told me. En route he achieved much more. Hold that thought.

“Rich stood out with his attitude,” said Lange, 81, still coaching after a half century. At the time, it was common for high school runners to jump into road races during the season. Their high mileage — as much 100 a week for Kimball at one point — supported it. “I recall one time Rich showed up for the Pepsi 20-Miler,” said Lange. “He arrived just before the race, nonchalantly ran 1:53, got in his car, and went home.” Under Lange, young Kimball at the outset ran about 65 miles a week, thriving on hill circuits and long runs along the American River trail. He had teammates to pair up with, like a kid named Hugh Miller, who set age-14 and high school freshman records for the marathon, running 2:43:40 in his first attempt, in 1971. As a sophomore, Kimball ran a 9:28 two-mile and, noted Lange, he was not yet physically developed. “He looked like an eighth-grader,” Lange said. “Walt really worked me,” said Kimball, who was always confident in what he could do and looking for more. “I was ready to explode.” With a family move to the city of Concord, northeast of San Francisco, more than an hour away, Kimball unleashed his pent-up powers at another all-boys parochial school, rival De La Salle, in his junior and senior years. Kimball pretty much trained himself. On dirt tracks, he devised workouts like 10 x 880, the first nine in 2:10, the last in 2-flat; and 20 x 440, the first 19 in 63, the last one in 53. On the roads, Kimball hooked up with another budding hundred-mile-a-week man, Mitch Kingery, of nearby San Carlos High, who ran a 9:09.4 two-mile as a sophomore. While in their teens, they held their own against post-collegiate runners. In one 20-km, Kimball took second overall in 64:19, with Kingery a close third. While Kimball never got around to running a marathon., Kingery made that his calling card. That same sophomore season, the precocious Kingery set a high school record of 2:23:47. In one stretch, Kingery ran four marathons in six weeks. As Kimball put it, summing up the running zeitgeist at a time when mileage was king, “We were 17. We would do anything.” Kimball, 67, still lives in northern California, in the town of Auburn, where the fabled Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run finishes, as though a paean to his past. He and his second wife, Haven, have five children and nine grandchildren in their blended family. Kimball is recently retired, having worked in law enforcement his entire career. For fitness, Kimball walks five miles a day, timing himself as in the old days. He tries for 15-minute miles, or about 1:15 total. His drive has sustained him.

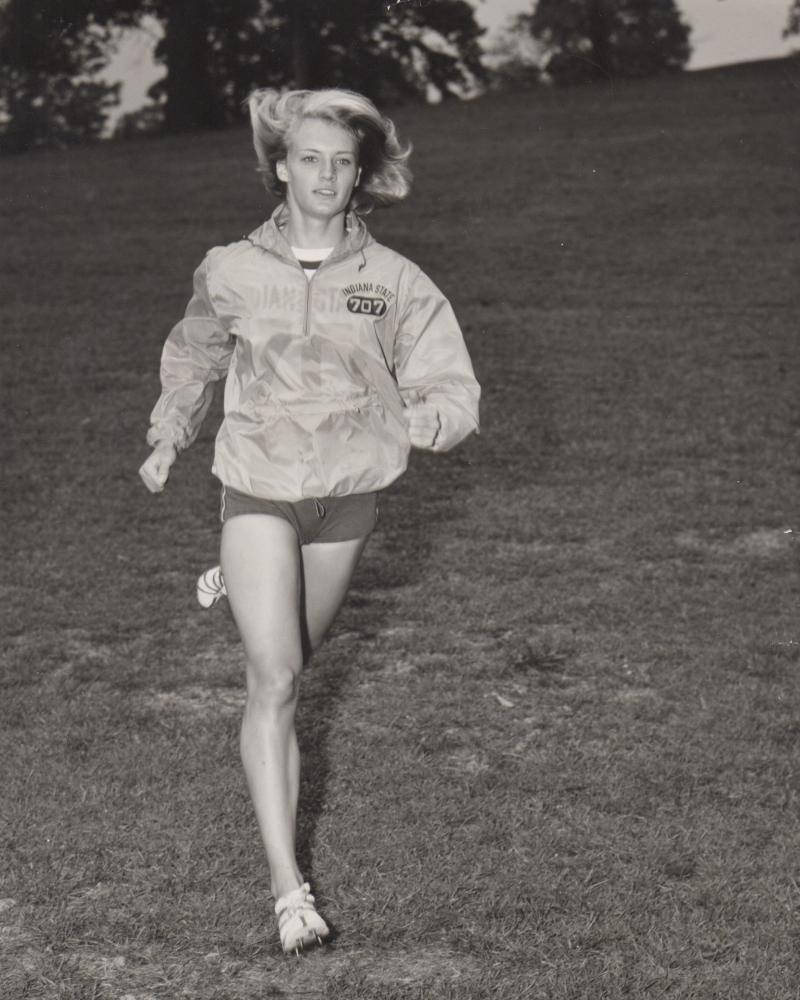

Monza, situated outside Milan in Italy’s north, on the way to the Lake Como resort area, would prove to be a world championship turning point for the United States. In 1973, the IAAF (now World Athletics) codified the long-running (since 1903) “international” Cross de Nations by making it the first official World Cross Country Championships. That year, it was held in Belgium. Twenty-one countries took part. The U.S. did not send a senior or junior men’s squad to Belgium. In a rare display of partiality (if it was that), the U.S. did field a women’s team, which won the bronze medal behind England and Finland. Doris Brown Heritage, a five-time winner of the “old” International, led the Americans in 15th place. The next year, in 1974, the senior men again stayed home, while Kimball’s junior contingent, along with senior women, were sent to Monza. The absence of senior men was striking, if not mysterious, given that the top performers in the late ’73 AAU cross country championships, at Gainesville, were gold medal material. Frank Shorter won the 10-km race for his fourth straight title, with luminaries like Doug Brown, Dick Buerkle, Barry Brown, Jack Bachelor and Marty Liquori placing in the top ten. It could well have been that these heads of state had bigger fish to fry on the track and roads. If so, it’s doubtful the penny-pinching AAU would have spent additional funds on sending a second-tier squad abroad. The U.S. women saw AAU frugality up-close-and-personal. While Francis Larrieu Smith was the reigning women’s AAU cross country champion from Albuquerque (the national events were held separately then) she, too, did not go to Monza because U.S. officials insisted the six female athletes pay their own way. The prior year, with the same AAU policy in effect, Smith had made the trip to Belgium, placing 16th right behind Heritage; but this AAU act was getting old and Smith was fed up. With the authority to speak out as the national titlist, Smith was quoted as saying at the time: “I want to go badly. I’m No. 1 and I’m in great shape. Why should I have to pay? I’m a member of a United States team. It’s ridiculous. Somebody has to stand up and protest.” Smith’s AAU tongue-lashing fell on deaf ears, even among her compatriots, all notable racers. The U.S. sent a six-women squad composed of Julie Brown, Cheryl Bridges, Vicki Foltz, Brenda Webb, Katy McIntyre and Clara Choate.

Treworgy, now 76 and living in North Carolina, said that when confronted the AAU gave no reason for the insult. “There were few opportunities for women,” said Treworgy, who competed on five world cross country teams and was an early world record holder in the marathon. “This was our Olympics.” Treworgy was teaching in the early ‘70s, making about $8,000 a year. She had to fork over about a thousand-dollars for the trip, plus she was docked pay by her school board for unauthorized absence. As a result, did she run angry in Monza? “We didn’t think that way. We were happy to be there, happy to be included,” she recalled. Julie Brown felt likewise but had no financial issue. Only 19 at the time (there was no junior women’s division then), she said the cost was “finagled through her club.” Brown, now 69 and an attorney in San Diego, ran for UCLA and a club called Naturite. As a young, naive athlete who’d come from Montana, she said, her club coach “controlled everything,” and “I was like a horse with blinders on.” The AAU at the time was testing whether sending junior-age athletes abroad would reap any benefit while fostering goodwill with their international hosts. Coaches were tasked with assuring that a large group of American teen-agers, male and female together, would behave themselves and not cause embarrassment. The initial test came the summer before Monza when the AAU, for the first time, sent a junior track squad abroad for dual meets versus West Germany, Poland and the Soviet Union. The U.S. passed the competition test, winning all three meets in combined men’s and women’s scoring. The diplomacy test was a tougher act, as the Iron Curtain served up some of its worst stereotypes. In a Track & Field News story about the tour, titled “The Good, the Bad and Sometimes Ugly,” there were reports of roach-infested housing and lack of drinking water in Poland and a “ransoming” of team baggage, among other indignities, when departing Moscow. Remember, this was during the Cold War. In 1972, President Nixon made a ballyhooed visit to the Far East to try and open doors with Communist China. In 1973, the U.S. finally withdrew its troops from Vietnam. In 1974, Nixon went to Moscow for a Summit. Apparently, his bags got through unimpeded. Sports would always feel the period’s tensions. Brown, who was on the junior track tour in the 800, told me the Soviets confiscated U.S. athletes’ cameras and followed them everywhere. She also recalled that when she and her roommates were packing up to leave, a group of Russian female athletes snuck into their hotel and begged to trade for their Levis. “The Russians were scared to death,” Brown said.

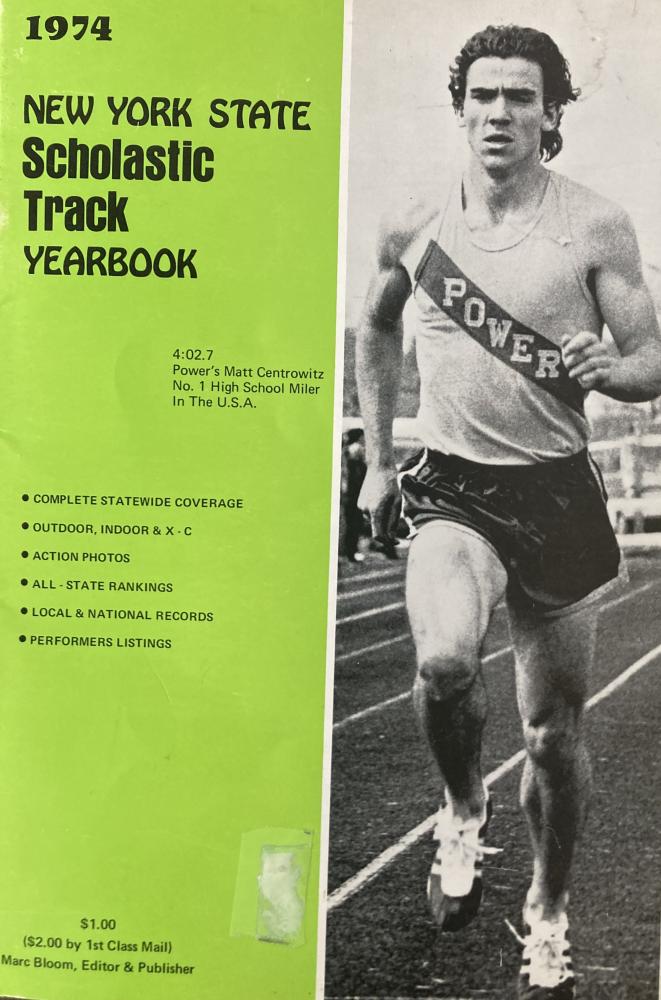

Centrowitz, building a reputation as a street-smart New Yorker with “A Bronx Tale” sense of humor, had earned a spot on the team with his 4:02.7 runner-up mile behind college freshman Mark Schilling at the AAU Nationals. Matt’s time was the fastest high school clocking in the country that season by almost three seconds and still stands as the New York State record today. Centrowitz had an excellent tour, winning the 1,500 in Germany over Schilling, while taking second to his older American teammates in Poland in 3:43.4 (equivalent to a 4:01 mile), and in Kiev, as well as rabbiting a 5,000 for victorious Craig Virgin against the Soviets. Centrowitz told me that any contact between the Americans and Soviets was forbidden, and so one night he was startled in an alley way when a local man purposely brushed shoulders with him while handing him a package, as in a spy scene from a Nelson DeMille novel. Opening the goods once safely at the hotel, Matt found a photograph of himself in the 1,500 with his name on the stadium scoreboard in Russian. “This guy took a big chance,” said Centrowitz, “and I never got to thank him.” Centrowitz came home with another memento from the trip. In the team’s “rathole” hotel in Warsaw, as he put it, locals were partying and the athletes couldn’t sleep. Matt stuck his head out of the window to complain and got smacked by a half-full beer can tossed from above. His forehead a bloody mess, Matt had to go find the team doctor to stitch him up. One of the tour’s assistant coaches, Elliott Denman, a journalistic colleague of mine from New Jersey who recently turned 90 — and was an Olympic 50-km racewalker in 1956 — assessed the track adventure as a success, with many of the young athletes going on to senior teams and big careers. But, he said, there was no end to the paranoia of his Soviet counterparts. In Moscow, the Americans’ departure for home was held up by hotel personnel conducting a count of every towel, as though one missing item could compromise Soviet security and start a war. The journalist and author Marc Bloom, whose career spans 60 years, contributes long-form historical articles regularly. His books include “God on the Starting Line,” about his coaching at a Catholic school, and “Amazing Racers,” about the Fayetteville-Manlius cross-country dynasty. In 2022, Marc was inducted into the Van Cortlandt Park Cross-Country Hall of Fame. More news |

The team uniform itself is a classic of the form, better-looking and better-fitting than many to come, and sweeter than some before like those hanging off slim American bodies two years prior at the ’72 Olympics. Color-wise, Kimball’s lavender Nikes were a good match, though, he told me, he usually ran in adidas.

The team uniform itself is a classic of the form, better-looking and better-fitting than many to come, and sweeter than some before like those hanging off slim American bodies two years prior at the ’72 Olympics. Color-wise, Kimball’s lavender Nikes were a good match, though, he told me, he usually ran in adidas. “I was very driven,” he told me, as though that explained everything. For Rich, “driven” did. It was a word he repeated when pressed for his underlying enrichment. “Driven” had to do.

“I was very driven,” he told me, as though that explained everything. For Rich, “driven” did. It was a word he repeated when pressed for his underlying enrichment. “Driven” had to do.  Kimball attended all-boys Jesuit High in the city of Carmichael for his freshman and sophomore seasons. He was developed by Walt Lange, an eminence grace of coaching who’s probably produced more great high school milers than anyone — Michael Stember, Mark Strangio, Michael Altieri, the Mastalir twins, Eric and Mark, to name a few — while his nationally-ranked Marauders once had a streak of nine straight state Div. 2 cross country titles.

Kimball attended all-boys Jesuit High in the city of Carmichael for his freshman and sophomore seasons. He was developed by Walt Lange, an eminence grace of coaching who’s probably produced more great high school milers than anyone — Michael Stember, Mark Strangio, Michael Altieri, the Mastalir twins, Eric and Mark, to name a few — while his nationally-ranked Marauders once had a streak of nine straight state Div. 2 cross country titles. In our talks, Kimball was affable and to the point. He was not one to embellish a story. That may come from his background as a sheriff. Just the facts, ma’am. He did volunteer that he has the Famous Photo from Monza set up for easy viewing in his office.

In our talks, Kimball was affable and to the point. He was not one to embellish a story. That may come from his background as a sheriff. Just the facts, ma’am. He did volunteer that he has the Famous Photo from Monza set up for easy viewing in his office. When I reached Bridges, now Cheryl Treworgy, for a clarification, she was in Eugene, Oregon, baby-sitting her latest grandchild, Grace, the daughter of her daughter, Shalane Flanagan — 2017 New York City Marathon champion, 2008 Beijing Olympics 10,000-meter silver medalist and 2011 World Cross Country bronze medalist, an extraordinary trifecta.

When I reached Bridges, now Cheryl Treworgy, for a clarification, she was in Eugene, Oregon, baby-sitting her latest grandchild, Grace, the daughter of her daughter, Shalane Flanagan — 2017 New York City Marathon champion, 2008 Beijing Olympics 10,000-meter silver medalist and 2011 World Cross Country bronze medalist, an extraordinary trifecta. A U.S. teammate of Brown’s, Matt Centrowitz, a recent high school graduate soon to enter Manhattan College near his Bronx home (before transferring to Oregon), came prepared with jeans to sell on the black market. He used the rubles he earned to purchase gifts for friends and family back in New York.

A U.S. teammate of Brown’s, Matt Centrowitz, a recent high school graduate soon to enter Manhattan College near his Bronx home (before transferring to Oregon), came prepared with jeans to sell on the black market. He used the rubles he earned to purchase gifts for friends and family back in New York.