Folders |

Backstage With Untold Cross Country History: 50 Years Since Richard Kimball's World Junior Gold (Part 2)Published by

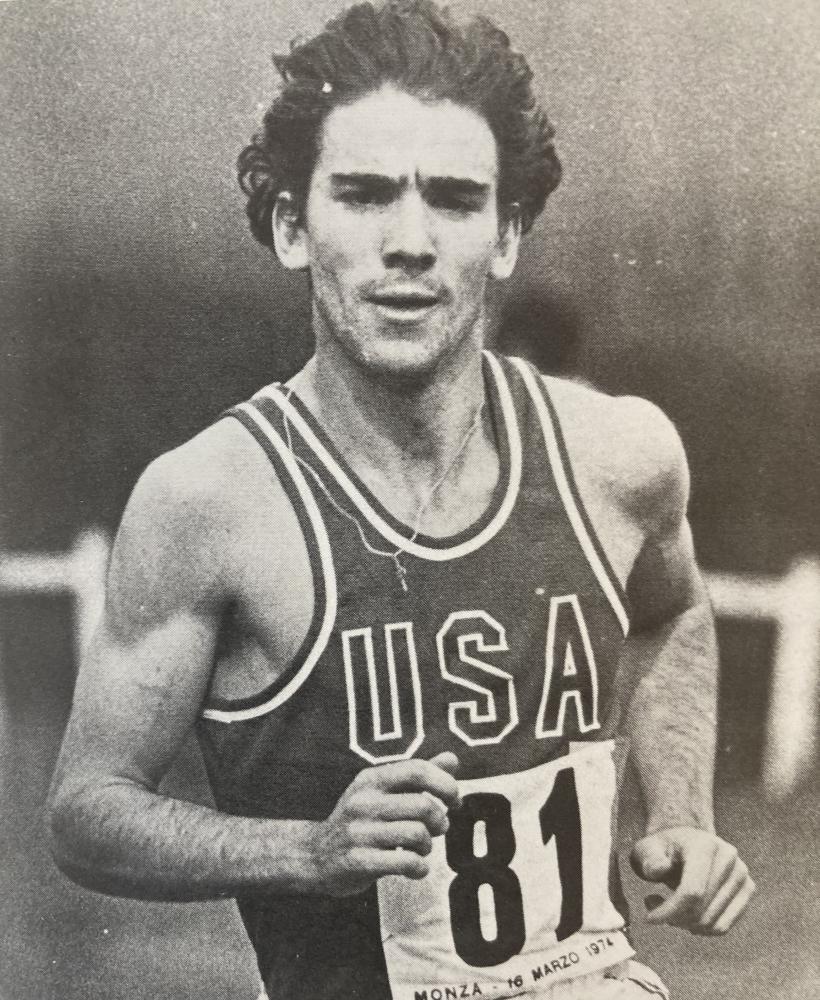

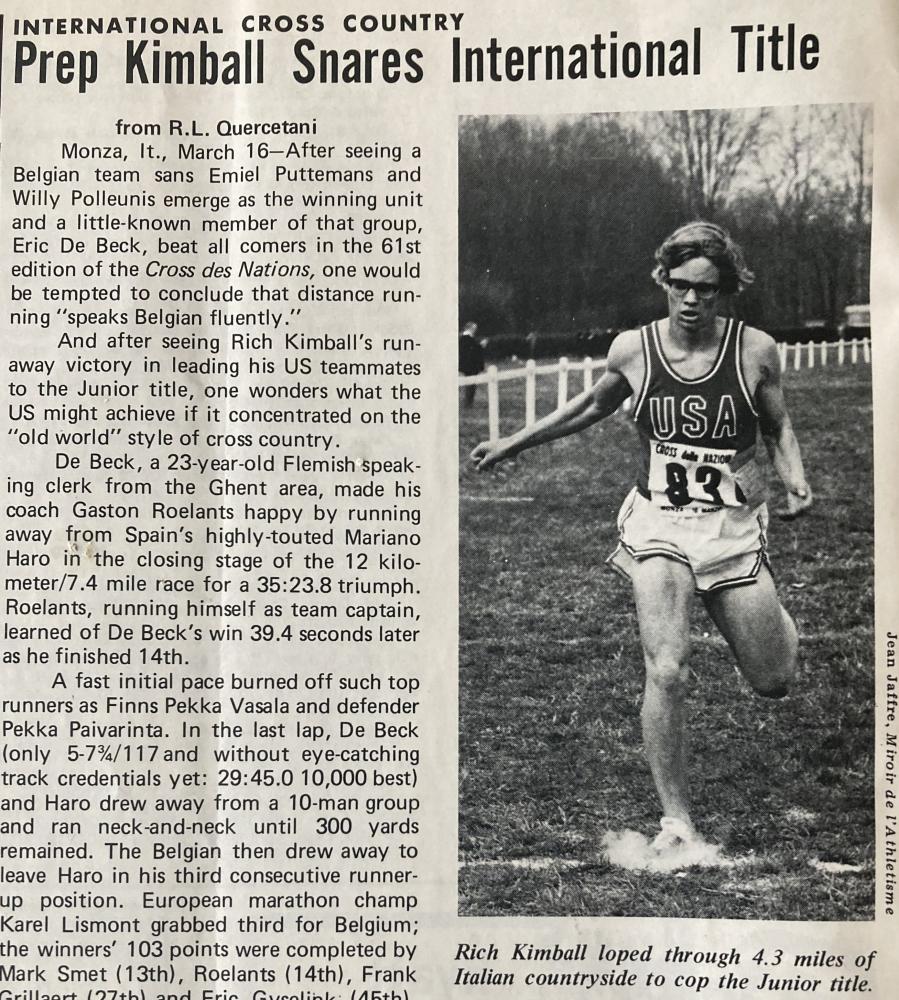

Missing the Gun, Winning the Chase —Richard Kimball and the USA Juniors Make History in ItalyBy Marc Bloom Part Two Eight months after the European junior track tour abroad and its oppressive Cold War security apparatus, Monza, in the Italian Lombardy region, decorated with stunning alpine peaks, presented a more inviting motif to the visiting American cross country athletes. Fifty years ago this week, the U.S. squad, six senior women and six junior men, gathered in New York, where they received their USA gear and pins for trading. They flew off to Milan with coaches Bob Campbell, a big wheel in the New England AAU, and Barbara Jacket, a long-time coach of NAIA power Prairie View A&M, in Texas. There would be no chance to adjust to the change in time zones. It was in-and-out: go, race, come home. While the women all knew one another and were savvy travelers, the men, except for Matt Centrowitz — who took charge immediately — were far less worldly but gamers with good credentials. The prior December, Richard Kimball, 17 — a senior at De La Salle High near San Francisco — had won a three-mile track race in 13:43.6 (sixth-fastest ever) and during the winter he’d run a high school indoor 1,500 record of 3:50.0 — this on the heels of an undefeated, record-breaking fall cross country season. John Roscoe was the ’73 JUCO cross country champion from Southwestern Michigan. Mike Pinocci, a future marathoner, also from the JUCO ranks (Odessa, in Texas), would be Kimball’s roommate in Monza. “Husky,” Pinocci said of Kimball. Pat Davey, a high school senior who would soon run a 9-minute two-mile, and J.J. Griffin, a college freshman at New Mexico, rounded out the team. It was a solid lineup. With little information to go on, it was hard to know which among the other 12 countries in the junior race — 10 from Europe plus Morocco and, oddly enough, Kuwait — would offer the Americans their greatest challenge. Europeans had a long cross country tradition and this was their turf: a horse track, Mirobello Racecourse.

Some of the women, the older ones in their mid-20s, adopted Matt, 19, as big sisters, charmed by his funny tales of New York and what-me-worry spirit. When Matt arrived in Monza having left his racing spikes at home, it was the women who took him into town by the hand to help him search for a new pair. “We combed the city looking for size-11 spikes,” said Treworgy, then 26. “I found a pair of Patrick's,” said Centrowitz, who probably would have run barefoot if he had to. “I never ran in them again.” Considering his age and experience, Centrowitz should have been rated the individual favorite. But while he’d excelled in his start at Manhattan College, he’d come to Monza exhausted from racing almost every week, fall and winter, for six months. “Mentally, I was a three out of 10,” he said. “I had to wing it and hope I wouldn’t blow up.” Kimball had no such concerns. He had not competed in three weeks and had a reservoir of sharpness from his track racing to cover any move. “I’m loosey, goosey,” he told me of his typical mindset. Whether competing in Monza or Modesto, Kimball’s goals seemed at odds with his psyche: big stakes were on his table while an aloofness governed his demeanor. Kimball’s ease complemented his drive. It was the perfect mind-body marriage. And whenever the gun sounded, he would say, as though primed to scatter at any moment like a startled cat, “I’m off.” Not this time. When the gun went off in Monza, Kimball, Centrowitz, practically the entire team, were facing the wrong way. The Americans were taking their sweats off when the starter gave final instructions — in Italian. “Pronti, partenza, via…” came the call. (Or something like that.)

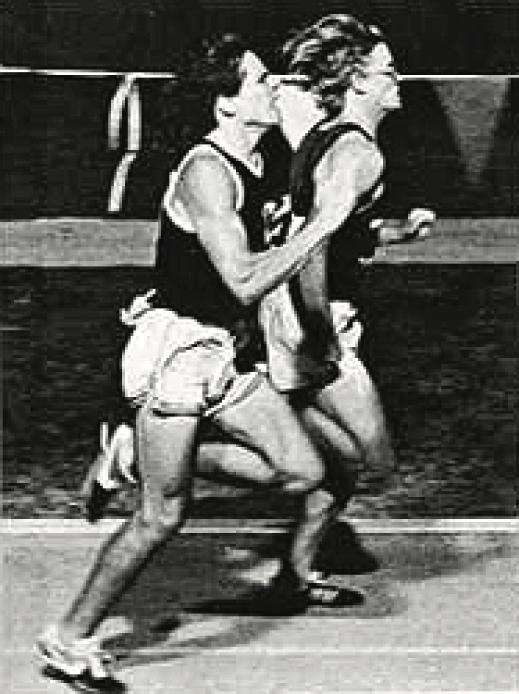

Kimball told me he’d heard that the Europeans liked to box out Americans, and now he had the whole field (except for the trailing Kuwaitis) wedging him in. After the initial shock, Kimball found room and moved up, forging a lead trio midway with Ortis and 16-year-old John Treacy of Ireland. In an email, Treacy told me that he ran 10 miles home every day from school at the time, raising more than a few Irish eyebrows. His formative daring would pay off. Treacy went on to capture senior cross country titles in 1978 and ’79 as well as the 1984 Olympic silver medal in the marathon. For his part, Centrowitz was unfazed, having had two testing college freshman seasons under his belt. With his strapping physique, he’d fought for inches in cross country congestion and on tight indoor tracks, counting on toughness to carry him through, especially on the lead-off leg of 4x800s. “I never choked, never had anxiety,” said Centrowitz, a 1976 Olympian in the 1,500 and one-time U.S. record holder in the 5,000. “That was the cornerstone of my career.” Gapped by the Kimball threesome, Centrowitz spent the second half of the race chasing after Treacy, all skin and bones, whose face showed anguish as he receded toward Matt, giving him hope for the podium. “I was hanging on the whole way,” Treacy said when I reached him recently on holiday in the south of Spain. “I knew that if I stayed with Kimball I would medal.” “I couldn’t believe it,” said Centrowitz. “I’m 19, 170 pounds, and this 90-pound little bugger is ahead of me.” Centrowitz’s assessment of Treacy’s size was not hyperbole. Treacy told me that in Los Angeles, in the Olympic marathon, he weighed 110. “In 1974,” he said, “I was certainly under 100.” The Monza course had everything cross country should have: long loops, short loops, hills, steeple-like barriers, turns, mud, a section in the woods. A crowd estimated at between 10,000 and 20,000 turned out, many shouting to Kimball as the “Americano” when he unleashed his decisive kick in the last half-mile. “I felt great,” Kimball told reporters at the time. “I turned it on as much as I could.” Kimball had lacked for nothing. In California, he’d been logging 15 to 18 miles daily, Monday through Friday, and a doing 20-miler on the weekend with one day off. He included hills and fartlek. He finished distance runs with long accelerations of 3 to 4 miles. On the home straight, after an elbow-to-elbow duel with Ortis marked by dazzlingly synchronized strides (the cover tells it), Kimball put himself 15 meters ahead of his rival and powered home to nail the world junior victory in 21:31. Ortis, 19, a future European 5,000 titlist, was second in 21:33 and Treacy third in 21:43. Centrowitz wound up fifth, a breath behind Dietmar Millonig of Austria, a future European indoor 3,000 champion. Roscoe, who’d led the field at 300 meters (apparently, he understood Italian), closed well for sixth. And with Davey, a Michigan high school star, 10th, the Americans’ four-man scoring tally of 1-5-6-10, for a low of 22 points, produced a world cross country team victory for the United States. The final U.S. runners across the line were Pinocci, 15th, and Griffin, 18th. None of the guys had expected a team victory. Everything was new. Every young man was a test unto himself, crossing the line from local boy in the States to international competitor. Up on the podium the athletes cherished the moment, winning as innocents, not so much for themselves as for their country.

Campbell collected the pieces. Did he take the broken prize home to fix? “I have no idea,” lamented Panucci, who went on to a bountiful road-racing career, winning the 1982 Barcelona Marathon, in 2:14:30. “We never saw it again.” There would be no trophy for the women’s team, which placed fifth. Choate, a teammate of Brown’s at UCLA, led the U.S. in 12th in the 4-km race. Brown, injured, could do no better than 27th. Bridges, 28th, and McIntyre, 31st, completed the scoring. Webb and Foltz placed 40th and 45th. England (38) won with Italy (50), Finland (61) and Belgium (97) next. If Smith had run for the U.S., which tallied 98, the Americans might have contended for third. Just so the women would have a story to tell, on the eve of departure, Bridges somehow got a key to the junior men’s quarters and, with Webb as an accomplice, short-sheeted their beds. Centrowitz, for one, slept like a baby. Story told.

The next year’s Worlds, at Rabat, the Moroccan capital, would showcase one of the best American international achievements ever. Julie Brown, only 20, captured the world title while leading the American women to the team championship. “The incentive was there,” she told me. Brown would become a top marathoner, taking second in the first U.S. Olympic marathon trial for women, in 1984, behind Joan Samuelson. Bobby Thomas, 18, won the ’75 junior race by 18 seconds and he, too, led the U.S. to victory. Thomas, from southern California, told the LA Times that the Runner’s World cover of Kimball was what inspired him to try and make the U.S. team; and he proceeded to win the AAU trials race. Thomas would have a short-lived career, however. He ran for three different colleges and once home from Rabat continued a busy racing schedule while training up to 120 miles a week. Injuries did him in. Kimball’s notoriety also spurred Ralph Serna, who’d placed fourth in the junior trial for Rabat. The AAU bureaucrats (them again) told the entrants that only four of six athletes on the men’s junior squad would get their trips paid for. “I knew that if I didn’t get fourth,” Serna told me, “I was not going.”

Serna, the nation’s No. 1 high school miler that spring, was so desperate that, unable to lift his legs over the barrier, he came to a stop and threw his legs over sideways, one at a time, as though climbing a fence, apparently allowed (see photo). Kissin passed him to the finish but Serna held off Hulst (who chose not to make the trip) for the fourth and last paid allotment. Too bad about Hulst. With his upcoming 29:11.2 10,000 meters (faster than Gerry Lindgren had run in high school), Hulst would have been perfectly at home in the 7-km junior championship. After the victorious Thomas, teenagers Clary, Kissin and Serna placed fifth, eighth and 15th to give the U.S. a repeat junior team championship, by six points over the Treacy-led Irish squad. Two years: Two U.S. junior teams, two individual and team golds. In 1975, the senior men, finally in action, were planting the seeds of gold. None other than Bill Rodgers took third (he would win the first of his four Boston Marathons a month later) and Frank Shorter finished 20th, in between his Olympic marathon victories (I don’t count drug cheat Cierpinski as “winning” in ’76.) The U.S. men placed fourth in team scoring.

In 1976, at Chepstow, Wales, Hulst’s moment arrived. Slashing age and high school class records at all distances at home (and his trip paid for), Hulst raced to victory, as recent high school indoor mile record-breaker Thom Hunt of San Diego — 4:02.7, which would stand for 25 years — placed second and Alberto Salazar fifth. With Don Moses in eighth, the Americans captured the team title with a near-perfect 16 points. They were the “East Africans” of their day. It was probably the greatest junior quartet the U.S. ever assembled. The four scorers were high school boys, all but Salazar from southern California. These were their two-mile times that season: Hulst, 8:44.6, No. 1 in the country; Hunt, 8:45.2, No. 2 in the country; Moses, 8:52.6; Salazar (of Massachusetts), 8:53.6. The American siege went on. In 1977, at Dusseldorf, West Germany, the fourth year of American junior superiority, victory went to Hunt, spearheading another U.S. team championship. Hunt went on to become a top road racer while competing on two USA silver-medal winning senior teams, in 1981 and 1983. Four years: Four U.S. junior teams, four individual and team golds. When Kimball returned home that spring of 1974, his main goal, the one that had possessed him for a year after his ’73 injury, awaited him: the state championship double. He proceeded to contest perhaps the most prolific high school track season ever. He did much of it in pain. Three months, 52 races, Kimball said. Is that enough to cause pain? Starting in mid-April, about a month after Monza, Kimball raced invitationals and championships every weekend through June, often doubling, tallying some two dozen competitions, and mid-week, in dual-meets, he often ran four events, easily topping 50 races by season’s end. Kimball did not wait until State to run a searing same-day double. His spring ’74 highlights in the mile and two-mile leading up to the state finals looked like this, courtesy of Track & Field News long-time high school boys’ editor Jack Shepard: — April 20: Downey Inv., Modesto 4:11.9, 8:57.4 — April 27: El Cerrito Relays 4:08.7 — May 4: Castro Valley Inv 4:02.6, 8:51.0 — May 10: Catholic League, Berkeley 4:08.7, 8:55.1 — May 17: No. Coast Sect Div, Hayward 4:09.2, 8:55.0 — May 25: No. Coast Sect Final, Kentf’d 4:02.4, 9:12.1 — May 31: State Champs qual, Bakerf’d 4:12.8 Kimball picked up shin splints three weeks before state. His coach at De La Salle, Ron Staszkow, taped him up but, recalled Rich, “the pain was excruciating.”

Kimball then rushed to get an icepack for his legs. An hour later, he lined up for the mile. “I had no tactics. I went in cold,” he said. Andy Clifford of Sunny Hills High in Fullerton, as expected, would present the only possible barrier to Kimball’s sweep. Kimball raced ahead, with Clifford close behind. “I wasn’t sure I could even run with my shin splints,” Kimball recalled. It’s been shown time and again that will can conquer pain. Kimball had the will. It had been percolating for 12 months, nurtured at Monza, propelled on the Nor Cal circuit, lavished in the state mile an hour before. Now, Kimball’s will flowered into a consuming drive. With 600 to go, Clifford moved to Kimball’s side, and the pair waged a singular duel for a lap-and-a-half, one still talked about in California and wherever athletes, a half-century later, reminisce about the great ones. A few tall tales might be told, but this one stood on its own. Kimball and Clifford stride for stride. They hit the three-quarter in 3:10.1. Then, almost a second race began — a Ryun-like final lap in full sprint. “I had to dig deep to stay with Andy,” said Kimball. “The emotion was overwhelming.” God only knows — with thousands of miles in his legs and scores of races in his soul since Kimball made the state-meet vow of ’73 — how he could stay on his feet, let alone run the toughest quarter of his young life. “I just got him,” said Kimball. “I kept my promise to myself.”

“Relief,” said Kimball in summary. On his victory lap, the Bakersfield crowd stood and applauded. Stats can be deceiving but not here. That season, Kimball ran the four fastest miles in the country: 4:02.4, 4:02.6, 4:05, 4:06.6. He ran the fastest two-mile, from state, 8:46.6, and had three of the next five fastest times. His California state double has never been equaled — not with the mile and two-mile only an hour apart. (In 2008, 34 years later, in a double that was superior in race time but not recovery time, German Fernandez won the state 1,600 in 4:00.29 and, three hours later, the 3,200 in 8:34.23.) But Kimball was not finished. Four more weeks. Fourhmore meets. Four more cities. Five races. Three defeats. One major victory. And then, some months later, a race against Steve Prefontaine. Hold that thought. Kimball won the mile at the International Prep, outside Chicago, in 4:07.3, then took seventh in the two-mile in 9:15.3. He ran the AAU Junior Nationals 5,000 in Gainesville, taking second in 14:22.0 as the win went to Serna in 14:16.2. The latter was the qualifier for the U.S. vs. USSR junior dual-meet in Austin, Texas, two weeks hence. In between, Kimball ran the Golden West in Sacramento, taking second in the 1,500 in 3:48.9. Three consecutive defeats? “I should not have been racing,” said Kimball. Kimball had a bit more drive left in him. In Austin, Kimball was peeved that press reports hailed the Soviet distance men at the expense of the Americans. Just don’t tell the young man he couldn’t do something. After Hulst, at 16, disposed of the Soviets in the 10,000, Kimball and Serna set up for the 5,000, planning to work together. With two laps to go, and the U.S. pair well ahead, team coaches on the infield called out to the Californians to “tie.” Heeding that call, Kimball and Serna ran the last quarter not quite all-out to gauge a shared finish. Kimball couldn’t stand holding back as the tape neared and inched ahead for the second international triumph of his high school senior year, in 14:26.8. Serna was a tick back in 14:27.2. The first Soviet was 30 seconds behind; the second almost a minute back. Combined men’s-and-women’s scoring gave the U.S. a 197-181 victory. No one at the headquarters hotel counted the towels when the Soviets checked out. High school was over, but not its spirit. Every college one could think of recruited Kimball. He chose Oregon State, for its noted coach, Berny Wagner. Kimball might have gone to Oregon but with Prefontaine (he was already graduated but training on campus) there and taking up the oxygen, said Kimball, “my ego got in the way.” To which, he added, “I regret that.” Soon, Wagner, a native Californian who produced numerous stars at Oregon State, left for Saudi Arabia to help develop that nation’s track-and-field program. Kimball, in turn, would transfer to San Jose State. But let’s not jump ahead. Prefontaine. Pre. And Matt Centrowitz: him again? Every fall, Oregon State and the University of Oregon played the annual “Civil War” football rivalry, which alternated between Corvallis and Eugene, about 40 miles apart. In 1974, the game was held in Corvallis. To mark the occasion and raise funds for charity, a Ducks vs. Beavers 40-mile relay was also held annually over the course of two days. It was a big fraternity event, not a serious “race,” but this time around it became serious. Centrowitz’ success as a Manhattan freshman did not sit well with some of his older Jaspers teammates. Uncomfortable with the situation in the Bronx, and after meeting Oregon coach Bill Dellinger at the NCAA cross country meet in Spokane, Wash., Centrowitz decided to transfer to Oregon after that first year, resulting in the required collegiate year-in-wait to suit up as a Duck. When Centrowitz (whose son, Matthew, would also run for Oregon and capture the 2016 Rio Olympics 1,500 gold) arrived on the Eugene campus in the fall of ’74 to start classes and train with the team, Dellinger set him up in an apartment with a couple of Oregon runners — Mark Feig and Steve Bence — and got him a job in a lumber mill for five dollars an hour to make ends meet. Matt would go running with Pre. They did track workouts. They would talk. They trusted one another. Feig and Bence got to talking about how cool it would be for Pre to anchor the relay — which some called the “Great Race” — but their pleas to Pre failed. After all, why would the man who’d never lost a collegiate race at Oregon, who’d won seven NCAA titles and set American records in every distance event, from 2,000 to 10,000 meters, who’d taken fourth within a nose of a medal in the 1972 Olympics 5,000, run a fraternity event? (In a culture war of another kind, four years later, fraternity life would be forever stigmatized by the making of the film, “Animal House,” on that very Eugene campus.) Go, Pre? There was only one gentleman who might be able to convince him: Centrowitz. The wise-guy New Yorker who’d learned how to make someone an offer he couldn’t refuse was up for the job. While there seem to be differing accounts of who actually got Pre to run, Centrowitz insists that after being asked by Feig and Bence to appeal to Pre, “I sold it to him.” Centrowitz (who also ran the relay) said he told Pre that 35,000 fans in Corvallis would be screaming when Pre would enter the stadium in the lead on the anchor leg to sew up an Oregon victory. I asked Matt, “Why would 35,000 Oregon State fans scream for Pre, an Oregon runner?” Centrowitz replied, “I didn’t tell Pre they’d be screaming for him. I put a New York spin on it.” On the second day of the relay, the two teams began where they’d left off, on the shoulder of a road outside Corvallis. Kimball was still injured but assigned the Oregon State anchor leg. He’d met Pre at meets and relished the challenge. Pre was a 23-year-old college graduate with a mile best of 3:54.6. Kimball was an 18-year-old college freshman with a best of 4:02.4 from high school. Kimball shrugged off the disparity.

Prefontaine proceeded to run down Kimball with as much fiery determination as in any of his famous races and entered Parker Stadium in Corvallis a stride up on Kimball. There was screaming, alright. Pre, soaking up the adulation of Ducks fans in attendance, delivered Oregon the victory, by two seconds. (In a photo developed from film in his camera when he died in May of 1975, Prefontaine poses with Centrowitz, Bence and Feig). Forty miles, two seconds. The splits appear to be lost to history. The day was a split decision: Oregon State won the football game, 36-16. (Conference realignment threatens to end the rivalry, which dates to 1894). Kimball was resolute when we spoke about the match-up 50 years later, one engineered, at least in part, by his Monza cross country teammate with the Bronx accent and silver tongue. Concise as ever, Kimball paused and said: “As a college freshman, I’m racing Steve Prefontaine and it’s close. That’s a good day.” Kimball graduated from San Jose State in 1978. His college running was nothing to speak of because of lingering injury. An administrative justice major, Kimball went into law enforcement and had a 46-year career in the criminal justice system. He served as a sheriff in various departments, working his way up to lieutenant. He worked as a coroner investigating homicides with a medical examiner. In a can’t-make-this-up irony, “Richard Kimball,” played by David Janssen, was the name of the lead character in the 1960s must-see TV series, “The Fugitive,” which became the 1993 movie box office smash starring Harrison Ford. The character Richard Kimball: running from the law and ultimately found innocent. The runner Richard Kimball: who would become an expert in the field of “telling the truth.” After Kimball eventually left sheriff’s department work and went out on his own, he created a business in “behavior analysis,” in which he offered classes to police and others on doing criminal interrogations and determining “one’s truth-telling style.” The business grew and at the end of last year Kimball sold it. As he had prevailed in so much else, Kimball overcame a bout of a rare form of skin cancer about a decade ago. Considered grave, the disease was arrested with a new form of chemotherapy, along with radiation and surgery, giving Kimball new life, the bliss of long walks in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada and, if a reporter calls, touching reminders of the gifts of youth. Perhaps Paul Simon said it best in “Bookends” when reflecting on memory a half-century ago: Time it was/And what a time it was It was a time of innocence/A time of confidences Long ago, it must be/I have a photograph Preserve your memories/They’re all that’s left you Hold that thought. The journalist and author Marc Bloom, whose career spans 60 years, contributes long-form historical pieces regularly. His books include “God on The Starting Line,” about his experience coaching a Catholic school, and “Amazing Racers,” about the Fayetteville-Manlius cross-country dynasty. In 2022, Marc was inducted into the Van Cortlandt Park Cross-Country Hall of Fame. More news |

The way things were going with Centrowitz, one might have thought this was Van Cortlandt Park. Matt was always in his element. He led the guys out for a run around town, they got lost, no one spoke Italian, and everyone had a good laugh. One time, in the absence of the driver, Matt took command of the team bus. That was not a good laugh. But Matt’s la dolce vita won converts. “I looked up to him,” said Pinocci.

The way things were going with Centrowitz, one might have thought this was Van Cortlandt Park. Matt was always in his element. He led the guys out for a run around town, they got lost, no one spoke Italian, and everyone had a good laugh. One time, in the absence of the driver, Matt took command of the team bus. That was not a good laugh. But Matt’s la dolce vita won converts. “I looked up to him,” said Pinocci. Even Kimball was rattled. “It was a double rattle,” he said. “My first time in Europe and now I have to also play catch up.”

Even Kimball was rattled. “It was a double rattle,” he said. “My first time in Europe and now I have to also play catch up.” At a celebratory team dinner with Campbell, the world championship trophy sat gleaming on the table, flanked by bottles of beer. In the glow of victory, an un-attentive athlete’s long coat accidently swiped the trophy off the table and it crashed to the floor and shattered.

At a celebratory team dinner with Campbell, the world championship trophy sat gleaming on the table, flanked by bottles of beer. In the glow of victory, an un-attentive athlete’s long coat accidently swiped the trophy off the table and it crashed to the floor and shattered.  Just about every athlete from Monza went on to future stardom. Webb would win three NCAA championships at Tennessee, plus a pair of USA national titles, and was ultimately a member of nine world cross country teams, more than any other American, male or female.

Just about every athlete from Monza went on to future stardom. Webb would win three NCAA championships at Tennessee, plus a pair of USA national titles, and was ultimately a member of nine world cross country teams, more than any other American, male or female. In the Trial’s last 100, with a final steeplechase barrier to hurdle, a hungry Serna found himself in third, behind Thomas and Don Clary, with Eric Hulst and Roy Kissin “breathing down my neck and my tank empty.”

In the Trial’s last 100, with a final steeplechase barrier to hurdle, a hungry Serna found himself in third, behind Thomas and Don Clary, with Eric Hulst and Roy Kissin “breathing down my neck and my tank empty.” And about that trivia question (from part one): After the ’74-’75 Kimball and Thomas junior victories, such was the excitement in the ranks of the elite that every youngster wanted a spot on the world cross country team.

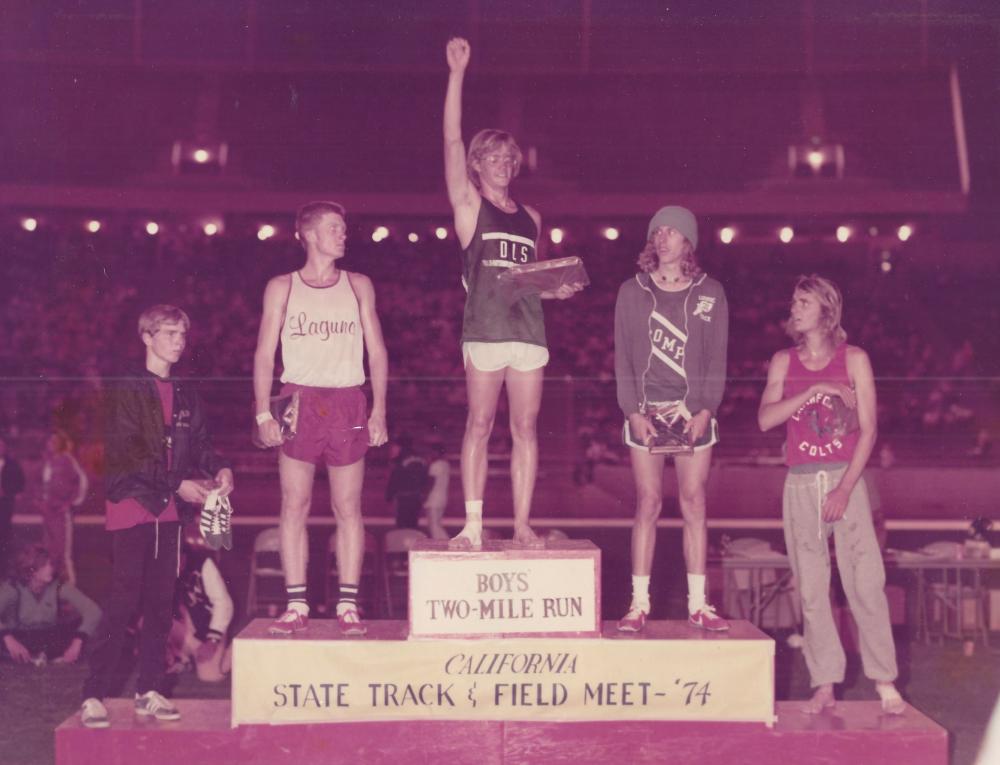

And about that trivia question (from part one): After the ’74-’75 Kimball and Thomas junior victories, such was the excitement in the ranks of the elite that every youngster wanted a spot on the world cross country team.  Undeterred, on June 1, Kimball first ran the state two-mile. “A lot of good runners,” said Kimball, “but I was fresh.” As fresh as one could be with some 50 races in his legs and punishing shin splints. Kimball ran the first mile in 4:21.9, the second in 4:24.6, with a 62.8 last quarter, for an 8:46.5 victory. Hulst, in second, set a national sophomore record of 8:50.6.

Undeterred, on June 1, Kimball first ran the state two-mile. “A lot of good runners,” said Kimball, “but I was fresh.” As fresh as one could be with some 50 races in his legs and punishing shin splints. Kimball ran the first mile in 4:21.9, the second in 4:24.6, with a 62.8 last quarter, for an 8:46.5 victory. Hulst, in second, set a national sophomore record of 8:50.6. Kimball’s last quarter was 56.5 for a 4:06.6. Clifford split was 56.6. He was a hair back in 4:06.7. The next four runners all got under 4:10.

Kimball’s last quarter was 56.5 for a 4:06.6. Clifford split was 56.6. He was a hair back in 4:06.7. The next four runners all got under 4:10.  With Oregon State varsity runners filling out the Beavers’ lineup, Kimball received the hand-off with a 15-second lead over Pre, whose eyes shot daggers. He’d been assured by Matt and everyone else that he’d be given the lead.

With Oregon State varsity runners filling out the Beavers’ lineup, Kimball received the hand-off with a 15-second lead over Pre, whose eyes shot daggers. He’d been assured by Matt and everyone else that he’d be given the lead.